In the nearly two months since Vice President Mike Pence directed NASA to return to the Moon by 2024, space agency engineers have been working to put together a plan that leverages existing technology, large projects nearing completion, and commercial rockets to bring this about.

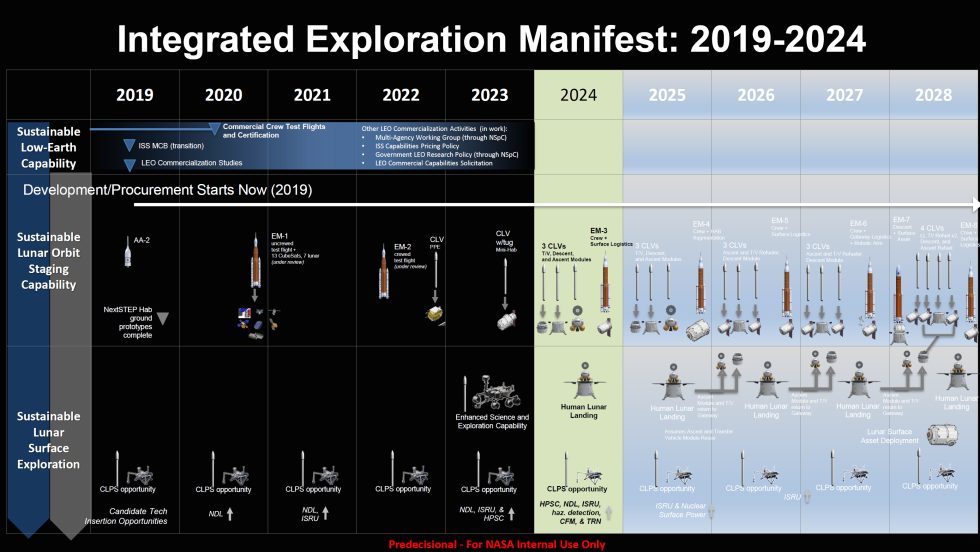

Last week, an updated plan that demonstrated a human landing in 2024, annual sorties to the lunar surface thereafter, and the beginning of a Moon base by 2028, began circulating within the agency. A graphic, shown below, provides information about each of the major launches needed to construct a small Lunar Gateway, stage elements of a lunar lander there, fly crews to the Moon and back, and conduct refueling missions.

This decade-long plan, which entails 37 launches of private and NASA rockets, as well as a mix of robotic and human landers, culminates with a "Lunar Surface Asset Deployment" in 2028, likely the beginning of a surface outpost for long-duration crew stays. Developed by the agency's senior human spaceflight manager, Bill Gerstenmaier, this plan is everything Pence asked for—an urgent human return, a Moon base, a mix of existing and new contractors.

One thing missing is its cost. NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine has asked for an additional $1.6 billion in fiscal year 2020 as a down payment to jump-start lander development. But all of the missions in this chart would cost much, much more. Sources continue to tell Ars that the internal projected cost is $6 billion to $8 billion per year on top of NASA's existing budget of about $20 billion.

The plan also misses what is likely another critical element. It's not clear what role there would be on these charts for international partners, as nearly all of the vehicles could—and likely would—come from NASA or US- based companies. An international partnership, as evidenced by the International Space Station program, is likely key to sustaining a lunar program over the long term in the US political landscape.

Three miracles

Although the plan is laudable in that it represents a robust human exploration of deep space, scientific research, and an effort to tap water resources at the Moon, it faces at least three big problems.

The first issue is funding and political vulnerability. One reason Bridenstine has not shared the full cost of the program as envisioned is "sticker shock" that has doomed other previous efforts. However, if NASA is going to attempt a Moon landing with this specific plan—rather than a radical departure that relies on smaller, reusable rockets—the agency will need a lot more money.

So far the White House has proposed paying for this with a surplus in the Pell Grant Reserve Fund. But this appears to be a non-starter with House Democrats. "The President is proposing to further cut a beneficial needs-based grants program that provides a lifeline to low-income students, namely the Pell Grants program, in order to pay for the first year of this initiative—something that I cannot support," House science committee chairwoman Eddie Bernice Johnson has said.

Congress also is not going to give NASA an unlimited authority to reprogram funds, with an apparently open-ended time frame, which Bridenstine has sought.

A second problem is that NASA's current plan relies on its contractors to actually deliver hardware. Boeing's work on the core stage of the Space Launch System is emblematic of this problem. The company has been working on the core stage for eight years, and it is unlikely to be ready for flight before another year or two. Boeing's management of the contract has been harshly criticized by NASA's Inspector General. After all this, can Boeing be counted on to deliver an SLS core stage in 2020, then again in 2022, and six more between 2024 and 2028?The big SLS rocket was supposed to have been fairly straightforward to develop, as it relied on space shuttle components, such as its main engines and solid-rocket boosters. By contrast, the three-stage, reusable lunar lander envisioned by NASA to get humans from the Gateway to the lunar surface will require new engines and systems, including fuel management at very low and high temperatures. Is five years enough time for this if it has taken NASA, Boeing, and the rest of the SLS contractors a decade to deliver the rocket?

Finally, NASA's architecture for a lunar return requires completion of a more powerful version of the Space Launch rocket, known as Block 1B, to be ready by 2024. In the new architecture, the SLS Block 1B booster carries a crewed Orion spacecraft to the Gateway along with "surface logistics"—likely air, water, food, and other consumables needed for a multiday journey down to the surface and back to the Gateway.

The key new technology in the Block 1B rocket is an upper stage, known as the Exploration Upper Stage, for which Boeing is also the contractor. In recent months, NASA has urged Boeing to complete the initial version of the SLS rocket and halted work on this new upper stage. Given Boeing's performance on the core stage, it is possible NASA may seek an alternative provider, such as Blue Origin with its existing BE-3U upper stage engine, to build the Exploration Upper Stage. This is a big ask for Boeing, Blue Origin, or anyone by 2024.

Three outcomes

So what happens next? NASA took a key technical step Thursday in awarding contracts for two of the three elements of its proposed lunar lander design. The more dicey questions will come in the political arena.

NASA is in danger of becoming a political football. Democrats are unlikely to support Pell Grants as a source of funding, and some space industry sources have speculated that this may have been a "poison pill" from the White House's Office of Management and Budget to undermine a long-term, costly program. If Democrats wanted to push back in a political way, they could tell President Trump they will only support NASA's lunar landing with Department of Defense funds earmarked for the "Space Force." Under such a scenario, the politicization of NASA would be bad for an agency that has mostly flown above the partisan fray.

And what happens if President Trump loses reelection in 2020? By early 2021, when a new administration moves in, it won't see much tangible evidence of a lunar return. The SLS rocket is unlikely to have made its first flight, there will merely be some drawings on lunar landers, and the Lunar Gateway will remain a year or two away from launch. This would make the lunar program very vulnerable from a funding standpoint, especially if the new president was more concerned about climate change and Earth science, and wanted to pivot toward a lower-cost space program that capitalized on the launch successes of the new space industry.

Finally, if the Trump administration wins, and truly cares about the 2024 landing—given the anemic $1.6 billion budget supplement, and tapping of Pell Grants it is far from clear it does—there is a path forward for NASA. With a more robust expenditure in fiscal year 2021, and some successes with the SLS rocket, it is possible that the agency could remain on a plausible path back to the Moon with this plan. It probably won't happen in 2024, as two sources told Ars the year 2026 is a more realistic date even given the new sense of urgency.

But at least, finally, there's a plan of record to debate.

https://arstechnica.com/science/2019/05/nasas-full-artemis-plan-revealed-37-launches-and-a-lunar-outpost/

2019-05-20 13:53:00Z

52780300290144

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar